Sergey Nechaev (b. October 2, 1847, Ivanovo, Imperial Russia -- d. November 21 or December 3, 1882, St. Petersburg, Imperial Russia )

The excerpts from Sergei Nechaev’s Cathechism of the Revolutionist (1869) that follow are often on my mind. Recent events in Tunisia and Egypt (leading to speculation about the possibility of similar uprisings occurring in other Middle Eastern countries), given their potential for breeding internal terror (filling power vacuums and structure voids), probably moved Nechaev's twenty-one incisive paragraphs to the very front of my brain.

Nechayev's remarkable Catechism inscribes (like a master engraver's burin) a clear and vivid picture of programmatic, systematic immorality.

Nechayev's remarkable Catechism inscribes (like a master engraver's burin) a clear and vivid picture of programmatic, systematic immorality.

Lucid and powerful, Nechaev's words and sentiments enumerating the "principles by which the revolutionary must be guided" could comprise part of a bizarro-Hallmark anti-Valentine’s Day series curated by Pol Pot -- one that might include his own haunting epigram: “Losing you is no loss; keeping you confers no particular benefit”.

Nechaev’s weird, sad, violent life ended at the age of 35 in a St. Petersburg prison cell midway through his twenty-year sentence at hard labor for killing I.I. Ivanov, a defector from the Narodnaya Rasprava (Nechaev's secret "People’s Reprisal") group.

Sergey Nechaev's influence continues today, a testament to our moral imperfections and failings and to his powerful writing.

Sergey Nechaev's influence continues today, a testament to our moral imperfections and failings and to his powerful writing.

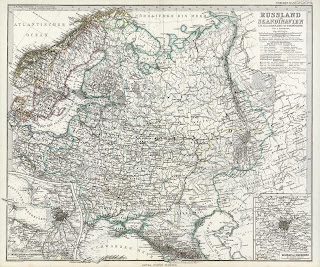

Map of Russia and Scandinavia, 1869

1. The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no interests of his own, no affairs, no feelings, no attachments, no belongings, not even a name. Everything in him is absorbed by a single exclusive interest, a single thought, a single passion -- the revolution.

2. In the very depths of his being, not only in words but also in deeds, he has broken every tie with the civil order and the entire cultured world, with all its laws, proprieties, social conventions, and ethical rules. He is an implacable enemy of this world, and if he continues to live in it, that is only to destroy it more effectively.

6. Hard toward himself, he must be hard toward others also. All the tender and effeminate emotions of kinship, friendship, love, gratitude, and even honor must be stifled in him by a cold and single-minded passion for the revolutionary cause. There exists for him only one delight, one consolation, one reward and one gratification -- the success of the revolution. Night and day he must have but one aim -- merciless destruction. In cold-blooded and tireless pursuit of this aim, he must be prepared both to die himself and to destroy with his own hands everything that stands in the way of its achievement.

11. When a comrade gets into trouble, the revolutionary, in deciding whether he should be rescued or not, must not think in terms of his personal feelings, but only of the good of the revolutionary cause. Therefore, he must balance, on the one hand, the amount of revolutionary energy that would necessarily be expended on his deliverance, and must settle for whichever is the weightier consideration.

Vera Zasoulich. attempted assassin of Gen. Fyodor Fyodorovich Trepov, head of St. Petersburg police, upon learning that Trepov had ordered Nechaev, a "political prisoner", beaten.

13. The revolutionary enters into the world of the state, of class and of so-called culture, and lives in it only because he has faith in its speedy and total destruction. He is not a revolutionary if he feels pity for anything in this world. If he is able to, he must face the annihilation of a situation, of a relationship, or of any person who is a part of this world -- everything and everyone must be equally odious to him. All the worse for him if he has family, friends and loved ones in this world; he is no revolutionary if they can stay his hand.

The younger Nechaev

15. All of this foul society must be split up into several categories: the first category comprises those to be condemned immediately to death. The society should compile a list of these condemned persons in order of the relative harm they may do to the successful progress of the revolutionary cause, and thus in order of their removal.

Catechisms Nos. 16-21 set and describe the "order of their removal" just referred to. The deviousness and venom they contain is breathtaking. Nechaev's "anti-tribute" to women, who are designated the "sixth, and an important category" for removal in Catechism No. 21, lingers in the mind. Interestingly, Nechaev accepts a woman's potential to equal a man in achieving a "real, passionless, and practical revolutionary understanding", therefore becoming the "most valuable of our treasures, whose assistance we cannot do without."

Catechisms Nos. 16-21 set and describe the "order of their removal" just referred to. The deviousness and venom they contain is breathtaking. Nechaev's "anti-tribute" to women, who are designated the "sixth, and an important category" for removal in Catechism No. 21, lingers in the mind. Interestingly, Nechaev accepts a woman's potential to equal a man in achieving a "real, passionless, and practical revolutionary understanding", therefore becoming the "most valuable of our treasures, whose assistance we cannot do without."

Nicholas II opens First Duma, Winter Palace, St. Petersburg, 1906

No comments:

Post a Comment